The Perspective Studio

A Collaborative Practice for a Fragmented World

by Johannes Jaeger and Marcus Neustetter

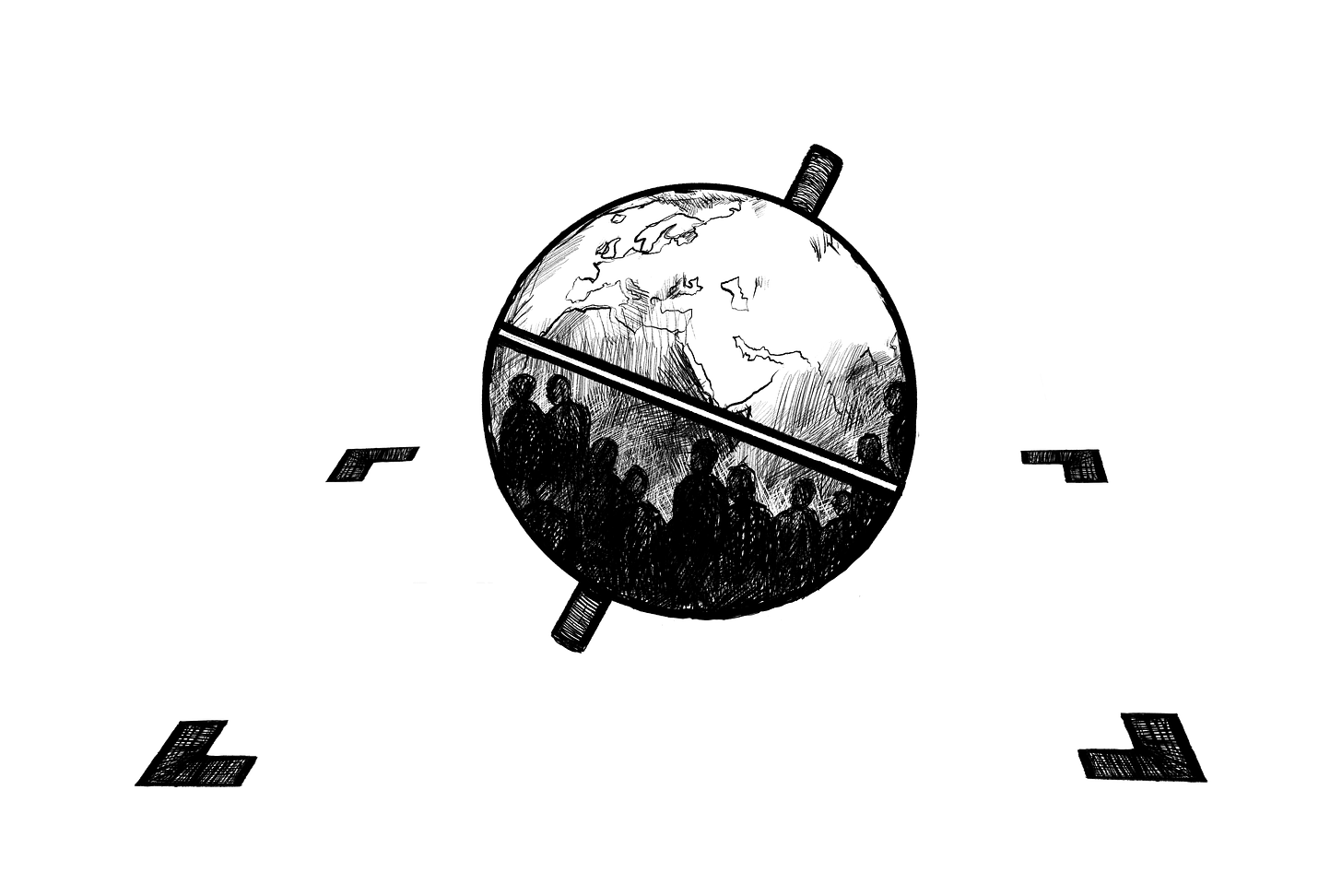

Sometimes, humanity feels like an enormous squabbling family.

We just can’t seem to get along. We talk past each other constantly. Yet, we are forced to share the same cramped and increasingly crowded home. The walls are closing in on us but there is no way out. So, we have no choice but to make this chaotic household work somehow — with the less-than-ideal company and the limited resources we’ve been given.

And, we can learn a lot from squabbling families — both about what works and what doesn’t. They can and do drift into abuse and dysfunctionality. But this happens surprisingly rarely considering just how much bickering is going on. So many families lovingly annoy the hell out of each other — disagreeing on everything, all the time. Still, family business gets done, and most of them manage to avoid descent into complete madness. How do they do that?

Can We All Agree That Consensus Is Overrated?

One thing is certain: families do not survive conflict by debating until someone has convinced everyone else of their superior wisdom. If society were a debate club, we’d be caught in a loop of eternal rebuttals: nobody scores any clear and lasting victories; somebody always dissents. Often, with ten people in the room, we get eleven opinions. And this is exactly as it should be.

A diversity of contradicting perspectives is not a bug, but a feature of any healthy human society — and of lived democracy in particular. No one has all the good ideas. Nobody has the solution to all our problems. No single strategy works everywhere. There is no perfect way to organize our lives and communities. Humans are imperfect creatures — that’s precisely why cultivating diversity matters. And it is where debating to resolve contradictions can get in the way.

To be clear, we are not against consensus, not against resolving contradictions. That would not be reasonable. Consensus is valuable — when it can be reached. It’s just that we’ve become a bit obsessed with it lately, as part of our urge to find an optimal solution to everything.

But we don’t seek diversity or contradiction for their own sake either. What we want is diversity that contributes constructively to society, and contradictions that move us forward productively.

This is where many contemporary discussions about “free speech” go off track. We should not and cannot tolerate the intolerable — as Karl Popper pointed out with his paradox of tolerance. According to German philosopher Michael Schmidt-Salomon, this isn’t really a paradox, but a false dichotomy. We can resolve it beyond binary thinking by distinguishing two boundaries:

The first separates what we can accept from what we must merely tolerate. Consensus only makes sense below this threshold.

The second separates what we can tolerate from what we absolutely cannot. This defines the Overton window of a society — the range of ideas that are open for public discussion.

The constructive diversity we seek exists inside this window, between those two thresholds.

But even these boundaries are up for debate, and we often fail to agree on where to draw them. The choice is deeply personal, shaped by context — culture, history, circumstance. Different groups of people, at different times, facing different problems, set these boundaries differently. And that is not just totally okay, but a core feature of communities that evolve and adapt.

When negotiating these boundaries, a different paradox of tolerance arises: we must often work with people we find intolerable. Again, this happens because we tend to think in binary categories and draw red lines around people rather than around their peculiar views.

It is a sad fact that a lot of folks hold opinions that come off as hateful, bigoted, misguided, deluded, or foolish. They clearly operate beyond the second threshold of any decent and reasonable human being. Or so you’d think. Because — and this should come as no surprise — they probably don’t see things your way, and think that it is you who are naive, arrogant, and acting in bad faith.

This is the state of our society today: tribalism, fragmentation, and polarization are all on the rise. We can hardly agree on anything anymore — not even on basic reality. How can we share our home like this? How can we still feel that we are all part of the same family?

What we need in this tricky situation is to rebuild and revive communities that cultivate a shared grounding in reality and a renewed will to co-create towards common goals, despite widespread and vigorous disagreement on how to get there. Our survival depends on this.

(In)tolerable Co-Creators

We are members of The ZoNE, a Viennese art-and-science collective, and we’re developing a portable laboratory or playground built on a new methodology designed to foster hands-on collaboration among groups of people with very different backgrounds, beliefs, and opinions.

We call this the Perspective Studio.

This studio uses art, science, and philosophy in a practical and playful setting to help participants work together on a shared project. The focus lies on reframing problems rather than solving them — harvesting rather than suppressing differences in opinions.

What we aim for is an adaptive approach to co-creation that is both flexible and compassionate, yet also makes sure we do not sacrifice our integrity, waste our time with people who have no intention of contributing constructively, or lose sight of our goals and core values altogether.

This approach is useful in many settings. Most prominently, it applies when a diverse coalition of people recognizes that there is a general problem, and that something ought to be done, yet, cannot agree on what exactly the problem is, how to tackle it, or what a satisfying solution would look like. Maybe there isn’t any — at least not one on which everybody can agree.

Take climate change or wealth inequality as concrete examples of such wicked problems. We disagree on how to proceed, and we can’t even settle on what a “solution” would mean — yet we mostly agree that doing nothing isn’t an option. So how do we move forward in such a case?

This is where things often get stuck. We get bogged down in futile debates. We play dirty tricks to block or neutralize each others’ initiatives. We create divisions where none need exist. Worse, we refuse to collaborate with those who agree with us on the specific issue at hand, but hold objectionable opinions on others.

In these cases, it can be more productive to decouple unrelated issues and to draw our red lines around particular views rather than entire people.

The crucial questions become:

Are the offending opinions directly relevant in the task at hand?

And even if they are, can we still collaborate with their holders without compromising our principles or condoning their views?

It also helps to refocus on what unites us: the shared recognition that doing something is better than doing nothing. Let’s get out of our heads and spring into action! And why sabotage one another if we can still work towards common aims? Contradictory approaches can coexist — as long as they do not obstruct or endanger each other. Live and let live.

In cognitive science, this idea is known as opponent processing. Contradictory thought processes don’t converge on a single solution, yet they carve out pathways that move us forward. These pathways open up opportunities — new questions to ask, new perspectives to consider, and sometimes even unexpected routes to the very solution we were seeking all along.

This highlights the importance of problem-framing over problem-solving. A problem may appear intractable simply because it is framed the wrong way. Before rushing towards solutions, we should pause and reflect on what is truly relevant to our situation.

Contradictory approaches are especially useful here: they reveal aspects of a problem we may have overlooked and allow us to explore a wider range of possibilities. Focusing too narrowly on immediate solutions blinds us to the richer landscape of alternative framings and opportunities.

An inspiring example of these principles in action is the Climate Majority project in the United Kingdom. Surveys show that roughly three-quarters of Brits are concerned about climate change, yet few believe that existing targets will be met. This project seeks to activate that silent majority into meaningful action — regardless of what participants think about immigration, taxing the rich, war in the Middle East, gender pronouns, or pineapple on pizza.

The point is simple yet profound: to address a specific problem, we don’t need to agree on everything else. Yes, everything in our world is connected — but that’s not the issue here. The challenge is to break up rigid ideological constellations so that we can act effectively where it matters.

Life is full of compromises. The key is to discern when compromise is wise, and when we must draw a firm line and defend that second boundary. This, too, is a personal decision — but one worth revisiting in each new situation.

None of these principles are merely theoretical. They must be practiced to be meaningful. And we need structured spaces to practice them well. The Perspective Studio provides exactly that: a safe environment for individuals and groups to explore the benefits and pitfalls of collaborative strategies for collective co-creation.

You can come to the studio — or we can bring the studio to you.

Wissenskunst: Serious Play with Ideas

Before we dive deeper into our methodology, you might be wondering: what does any of this have to do with a studio and with art? And that’s a fair question.

The most direct answer is this: the Perspective Studio uses the practice of collectively creating an artwork to move people from abstract argument into embodied, hands-on co-creation. But there are also two deeper reasons we ground our work in art.

The first is that art is uniquely sensitive and responsive to shifts in the shared sensibility of an age — what Michel Foucault called the episteme: the cultural medium that shapes our thinking and general being within a historical period.

Consider, for example, the emergence of the postmodern episteme. Its seeds were sown in the deconstructive tendencies of modern art — impressionism, expressionism, cubism, dadaism, and so on — which were really already postmodern in spirit. Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), a porcelain urinal displayed as an artwork, stands out as a pivotal gesture along this trajectory.

This radical questioning of artistic conventions was later echoed in the postmodern philosophy of the 1960s, which gained academic traction in the 1970s and 80s as “Theory,” and began influencing politics and culture — through wokeness and social-justice movements — by the early 2000s. Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian (2019), a banana duct-taped to a wall, serves as an ironic counterpoint to Duchamp, signaling that the postmodern episteme may have run its course.

This brief historical detour shows how art often anticipates broader intellectual and cultural shifts by decades. In that sense, we hope to use art as an early sensor for what might come after our current postmodern, and increasingly post-factual, era.

The second reason we express ourselves through art is to help humanity rediscover its vulnerability. We live in a time of relentless, shameless self-promotion. Art, though far from immune to this trend, remains one of the most powerful means of questioning and subverting it.

On top of this, centuries of material abundance and technological progress bred a dangerous hubris — especially among scientists, engineers, inventors, technocrats, and politicians. We’ve come to see ourselves as invincible, limitless, standing outside and above nature. But this illusion of power and control is cracking. Climate change, ecological collapse, political instability, and social unrest are converging into what some have called a metacrisis.

We’ve reached a kairos, or turning point in our history. But kairos not only means crisis in Greek, but also the right moment. As we’ve argued elsewhere, there are no quick technological fixes to our predicament. Instead, this is our chance — perhaps the last one — to change our attitude. What we need now is less hubris and more humility, a new awareness of our limitations.

With such radical uncertainty, we must learn to play again — with all aspects of our lives. That’s why we use the artistic concept of serious play to open spaces where we can share vulnerability, engage honestly and authentically, and rethink the wicked problems of our time.

To do this, we acknowledge the artistic process and pursuit in the studio — a site for experimentation where exploratory practice and permitted “failure” are essentials in the act of playing — a space that frames opportunity of play and the possibility of personal discoveries without premature scrutiny and judgement.

You might think of this as a more whimsical version of what educator and philosopher Parker Palmer calls circles of trust — spaces of deep listening and mutual recognition, as he discusses in his recent conversation with Andrea on Love & Philosophy. Or you might see parallels with philosopher Hanne De Jaegher’s engaged epistemology (also featured in one of Andrea’s recent podcasts), which views true knowing as a form of active, empathic interaction with others. There are also various episodes about paradox and play.

Serious play allows us to look at ourselves and others with sincere irony. Our play is serious because we strive to recognize each other for who we truly are. Only from such recognition can genuine co-creation arise. But our seriousness is also playful, because we know we’re not that important after all. We admit that we are wrong about many things, most of the time.

This is what philosopher and poet William Irwin Thompson called wissenskunst — clumsily translated as theory art: serious play with scientific and philosophical ideas that pushes the boundaries of what can be known in this age of crisis and opportunity.

Wissenskunst is not traditional art, science, or philosophy — nor a simple fusion of the three. Instead, it explores the in-between zone of existing institutions and modes of inquiry, harvesting synergies that only emerge at the interfaces between different disciplines and practices.

The Perspective Studio

How does all this work in practice?

The Perspective Studio is a facilitated process that we bring to community-centered contexts — corporate, academic, artistic, and beyond. It is a collective practice that reshapes itself around its participants and environment. It takes place in our studio, at event venues, in classrooms, public spaces, outdoors, or any other setting that inspires people to reflect and create together.

Within this broad framework, we support a wide range of activities. Sometimes, it manifests as a focused workshop that helps groups reimagine and reframe a wicked problem. At other times, it becomes the structure for a team retreat or public gathering that strengthens community bonds, or sparks grassroots activism. In educational settings, it allows students to engage hand-on with complex ideas in playful ways. In institutional contexts, it becomes a way to bring stakeholders into constructive dialog for collective decision- and policy-making. In academic environments, it can stretch into week-long inquiries that open new research avenues. And in longer-term collaborations, it provides a scaffold for developing strategic visions, new organizational structures, or networks of trust among change agents.

We especially enjoy situations that require transdisciplinary collaboration — bringing together artists, engineers, scientists, and philosophers. We help corporate customers engage with the arts, universities, museums, or other public institutions to integrate creative and scientific perspectives. And we translate abstract scientific and philosophical ideas — from a wide range of disciplines — into practical approaches for addressing urgent cultural and societal challenges.

Underlying all of this is a simple principle: everyone’s voice carries equal weight. Academic titles and professional hierarchies are left at the door of the studio so that the work can unfold openly.

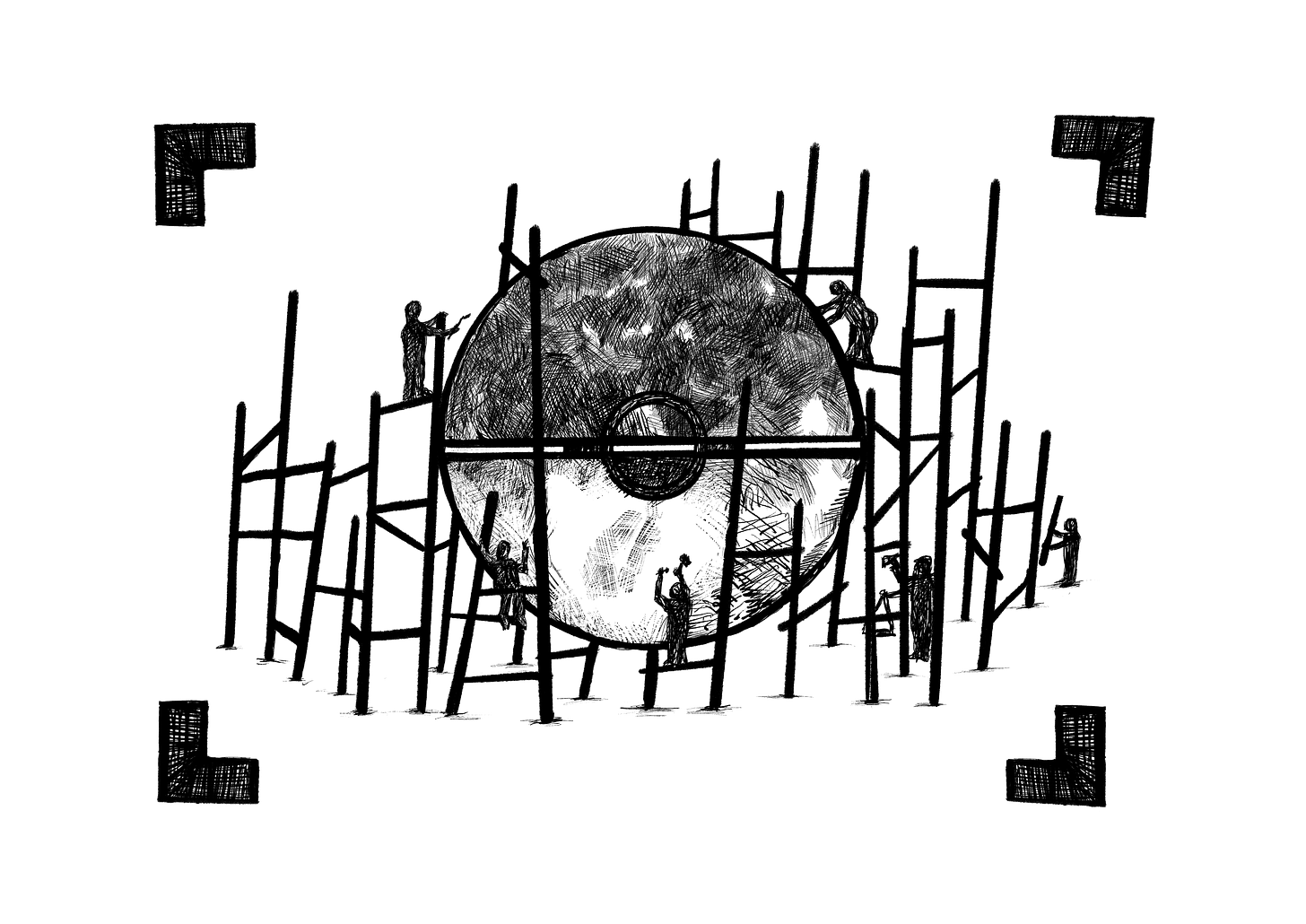

Each collaboration begins with a process of co-designing an environment and project — to shape an approach that fits the specific context. This often involves co-creating an artistic intervention or installation, drawing on practices from the visual arts to anchor the shared exploration.

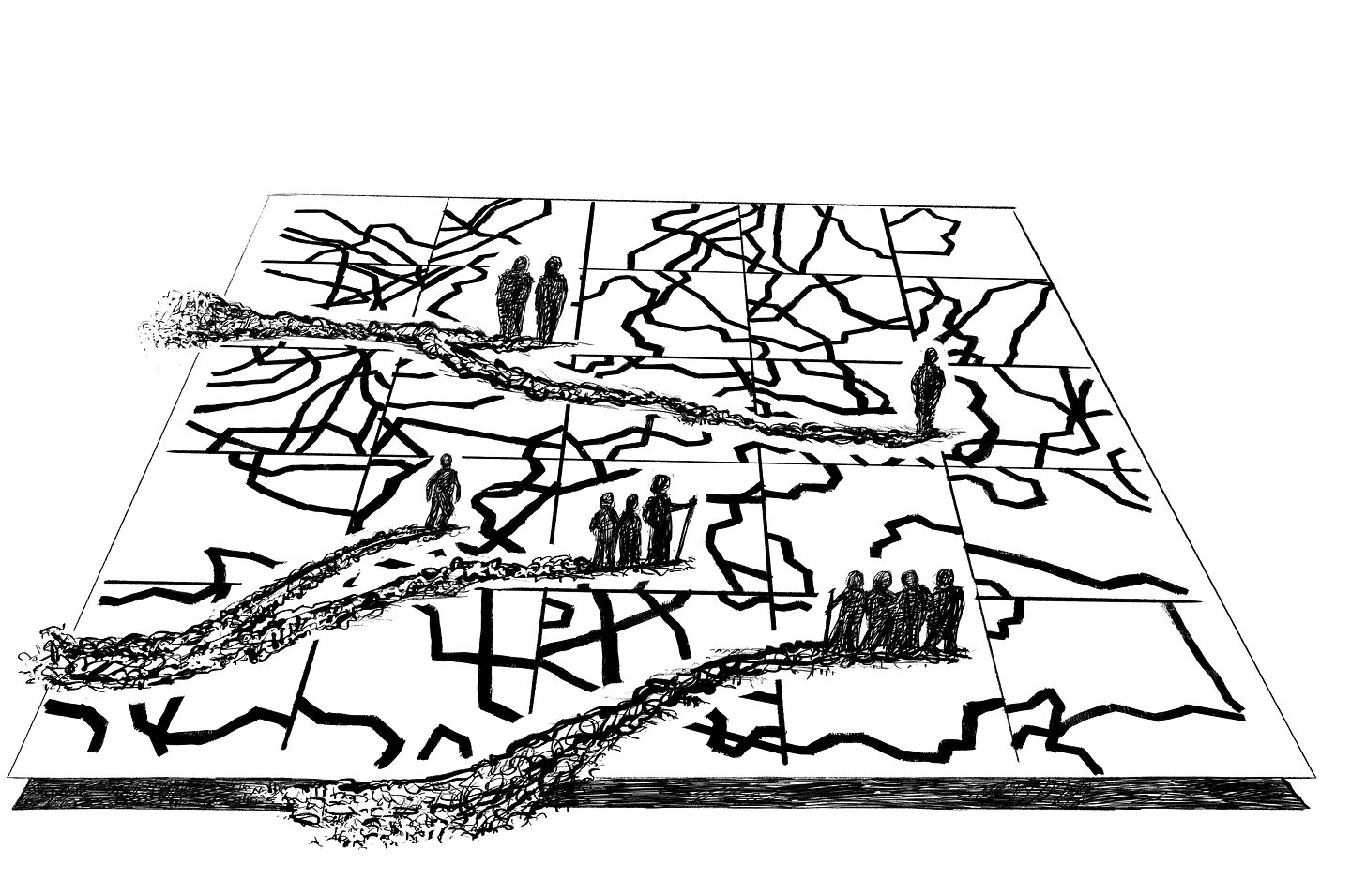

For instance, we often begin by drawing cognitive and conceptual maps together. These serve as both metaphor and method for exploring how limited beings like us make sense of the world. The practice draws on the science of embodied, enactive, extended, and embedded cognition — (4e) cognition — which reveals gaps and tensions between abstract mapping and the concrete territory of active explorative experience.

Rather than seeking an all-encompassing map that mirrors reality in all its glorious detail, we create a set of smaller, more specialized maps that are robustly useful for our particular purposes. Participants locate their own perspectives on these maps, transforming them into a constellation of interconnected personal narratives.

We then use these narratives in a process of deliberation — not to reach consensus, but to cultivate coherence through difference. The goal is to generate reframed understandings that weave diverse, even contradictory, viewpoints into a coherent but plural foundation for collective action.

This phase of our work is inspired by Nora Bateson’s methodology of warm data. It invites participants into context-shifting exercises and forms of serious play that move across perspectives. We explore each situation through multiple lenses — ecological, social, emotional, systemic — immersing ourselves in each to foster empathy, awareness, and nuanced insight into interdependence.

As the process unfolds, our initial maps evolve — they become three-dimensional, interwoven, and dynamic, reflecting the complexity of real relationships. What began as flat diagrams of a wall or floor transforms into a spatial network of ideas and connections, shaped by our collaborative engagement.

Throughout, we emphasize mutual understanding and hands-on co-creation, rather than persuasion using abstract argument. Participants explore overlapping interests, articulate their differences, and co-design strategies for collective movement forward, informed by their diverse lived experience.

An essential part of the journey is to acknowledge different forms of expression by making space for non-verbal exchange and acts of deep listening — listening not only to what is said but to embodied communication that emerges in expressive movement, collective construction, or actions that bring to the fore what we might not be able to put into words.

At the end, we reflect together on what we have created — the structure, installation, or perturbation that has emerged in our shared space. What hidden aspects of our collective work does it reveal? What insights does it contribute that we could not have expressed in words? And how does it feel to have built something together?

We often invite participants to keep parts of the co-created work as reminders of the process, and we document it through video and photography. What matters most, however, is not the artifact itself but the shared journey of making it.

Our process is designed with introverts in mind. We focus on group-based, practical activities rather than individual performance or presentation. This distinguishes our approach from traditional, discussion-centered workshops or those based on improvisational theater, which often emphasize communication and public expression.

Our facilitation strategies promote psychological safety for people — but not for their ideas. Through serious play and sincere irony, participants are encouraged to experiment boldly and to treat serendipitous and unavoidable “mistakes” as creative catalysts. We learn most when we can admit and embrace being wrong, both during and after the experience.

We continue to develop our methodology through real-world applications. So far, we’ve collaborated with a local Montessori school, an academic research project at the University of Vienna, the company ArtEO (as part of the Living Planet Symposium in Vienna), Ars Electronica and Johannes Kepler University in Linz (during their Festival University), the Learning Planet Institute in Paris, and the Centre for the Less Good Idea in Johannesburg, among others.

While we prefer to hold our studios in person, we also implement them online or in hybrid formats. This enables broad participation across regions and ensures global diversity and reach.

Building Together …

Where do we go from here? And why are we writing about this for Love & Philosophy?

For one, the Perspective Studio is more than a workshop format — it is a mobile and adaptive laboratory, a playground for exploring and transforming how we collaborate in a fragmented world. It is designed to test, refine, and expand the very practices we’ve been describing. And we’re looking for new contexts, partners, and communities in which to bring it to life.

So, if you feel that this methodology connects with your own work — if it resonates with issues you care about, or challenges you face — we would love to hear from you. Let’s co-create!

But, there is another, deeper reason we are writing this: we sense profound alignment between what we do and Andrea’s own way-making philosophy.

Waymaking, as Andrea describes it, is “the practice of holding space for one another as best we can,” while we navigate towards an unknown and unknowable future. To do this, we resist the urge to reduce everything to binaries — black and white, winning and losing, right and wrong.

As Andrea Hiott often reminds us on her podcast and in her writings, life itself is deeply paradoxical. To live it well, we must learn not to dissolve paradox, but to hold it. Only when we can carry contradiction — rather than escape it — can we move forward together, honestly.

This does not mean we should be lazy or inconsistent in our thinking. Far from it. There’s already enough careless confusion and wilful stupidity in the world. We still need to think carefully, to reason clearly, and to seek coherence where it can genuinely be found.

But even when agreement proves impossible — as it so often does in these bewildering times — we are still called to act. At this kairos in human history, our actions carry extraordinary weight. Every small act or creation, care, or courage ripples outward. The goal is not to think alike, but to move together — not necessarily in unison or harmony, but with shared momentum.

That is why we hope to establish a series of circles of trust with Andrea and her community, dedicated to the questions we most urgently need to face:

What are the essential roles of art, science, and a lived philosophy in these turbulent times?

How must these institutions transform themselves to fulfill these roles?

And how can they help us reconnect — with ourselves, each other, and reality itself — in a time of exhaustion and fragmentation?

What we want is not polite conversation that glances over our differences, but honest dialog that embraces them. Because there is beauty in difference — and in that beauty lies the possibility of futures we cannot yet imagine.

If any of this speaks to you — if you feel the spark of recognition or curiosity — we invite you to join us in one of our Perspective Studios some day soon.

Johannes Jaeger and Marcus Neustetter are members of the arts-and-science collective The ZoNE.

They are currently writing a book called “Beyond the Age of Machines,”

whose content they also make available, chapter by chapter, as video shorts and full-length videos.

Send us feedback or inquiries about collaborations or circles of trust at this email address.

Love and Philosophy would love to hear from you if you have practices or groups who are trying to find ways to hold paradox, which means to move beyond binaries without thinking one side has to win over the other, and to do this with care. This post is from one group trying towards all this. What do you think?

Johannes Jaeger and Marcus Neustetter are the authors and artists of this article; please only reproduce with their permission. This article is informational only and not meant as professional guidance or advice

Keen to follow along with this as there is significant resonance with the work I've been doing over the years. The points about paradoxical thinking, affording for complexity and provoking the limitations of pursuing consensus, learning through play, participatory sense-making and bringing scientists, artist, philosophers together is needed more now than ever. Maybe when timezones work I can join in on some synchronous play.

Exceptional framing of opponent processing in action! What really lands here is the shift from debating until consesnus to actively building with contradictions still intact. I worked on a municipal planning project once where we got stuck trying to reconcile neighborhood visions, but once we stopped trying to merge them and just built separate pathways that didn't block eachother, momentum came back fast.