Seeing what we don't see: As a Practice #14

Will we always have a blind spot? What practices can help us notice what we've missed?

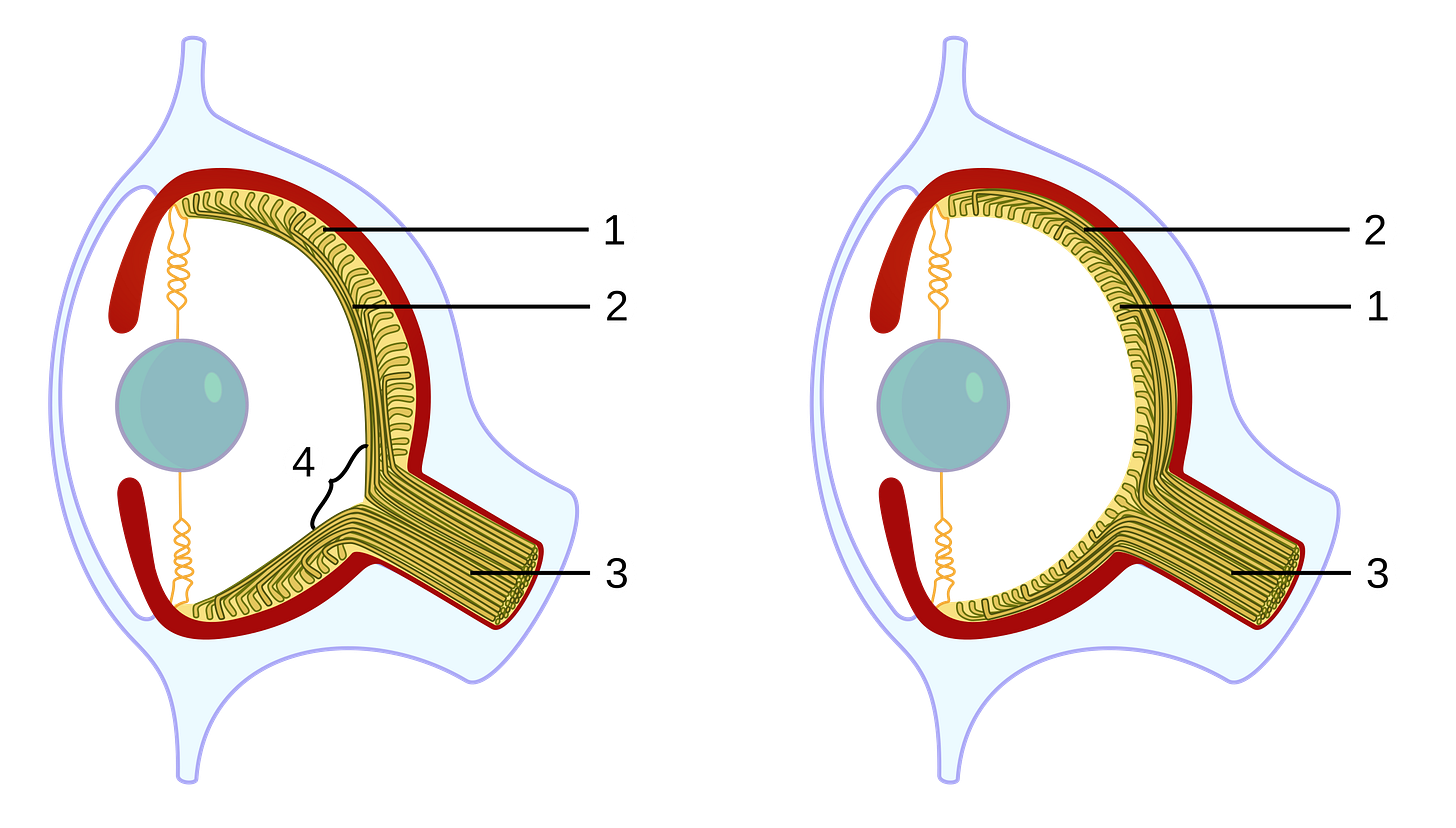

We all have a blind spot—a hole in our visual field where the optic nerve enters the eye. That means we are always missing something, and unaware that it is missing. This ‘missing vision’ comes about because of the way the optic nerve works, the place where fibers pass through the retina (see #3 below).

You can imagine it as a dark opening in the midst of a smooth curve of reflected light, a little tunnel into other realms. This blind spot is essential for us to be able to see, and yet, because there are no photoreceptors there, it means we are always missing a part of our vision: Somewhere right now, there is a gap in your vision—you just can’t see it.

It’s hard to think of a more literal and physical example of holding paradox than this—in order to see, there is something we are not seeing; in order to see, there will always be something we cannot see.

There are exercises you can do to bring this blind spot into view—to be able to see that you do not see. As you’ll experience if you try any of these, it can be shocking to observe how what is glaringly obvious from one point of view is literally invisible from another position.

I experienced this in my first cognitive neuroscience lab when the professor wrote something on the board and we students then did these special exercises as we moved through the room and watched as what he had written became invisible and then visible again.

Developing these blind spots (both the literal and the metaphorical) has taken history itself. Noticing them has likewise been a long process of scientific, philosophic and spiritual discovery. Still, in both the literal and metaphorical sense, knowing they exist is the first step towards avoiding the troubles they can cause. Only then can we practice ways of seeing what we cannot see.

In this week’s episode, philosopher Evan Thompson and I discuss his most recent book, The Blind Spot, written alongside Adam Frank, and Marcelo Gleiser. This book is mostly about the philosophy of science, but much of what we discuss relates to other areas of our lives as well, and we end up discussing practices that can help us address our shared urgencies.

As of now, there is no way for us to get rid of this literal blind spot. Could we get rid of at least the metaphorical blind spots?

Probably not, because as soon as we’ve corrected our inner vision, the potentials of that vision have shifted, as the encounter and all our life processes will also have shifted. In other words, as soon as we get rid of one metaphorical blindspot, another one will have been created, much like the experience I had in my cognitive neuroscience class as I moved around the room—the blind spot changes as we move.

Still, as Evan and I discuss, we can cultivate practices whereby we get better at noticing these blind spots, and we can address and alleviate many of their harmful consequences.

How? Here are some ideas Evan mentions in this episode:

learning how to tolerate uncertainty (a subject linking to the last episode)

learning a kind of ‘cognitive humility’ —a way of thinking does not take yourself too seriously but respects your position as embedded with other positions

learning how to remember that anything said is said by somebody in a particular context, and that has to reflexively be taken into account

The real trick is—we have to do it together.

My blind spots will never be the same as yours, because we are in different positions in space and time, we’ve had different trajectories of development and different paths in life, so we will always be able to see what another cannot see, and there will always be something we cannot see that another can.

Communicating these visions so as to uncover one another’s blind spots and thus extending our potential together might be the meaning of life.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Love & Philosophy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.